Project Layout - Survey Results and Updates

I’ve been working diligently for a few weeks on a formal description of a C++ project layout convention. Other than a few discussions on the C++ Slack, the first public announcements and discussions appeared in a Reddit thread entitled Prepare thy Pitchforks.

The informal proposal was well received, so I’ve based the working name from the title of the Reddit thread: Pitchfork.

The initial post spawned a lot of debate and questions from the community. There were several concerns from community members that I had not yet taken into account, and a few pointed out issues in my document that I hadn’t previously considered. It was clear that I had to make a lot of refinements for the informal standard.

A few weeks later I followed up with another Reddit post, Pitchforks Part II, which included an informal survey of the community regarding some contentious or undetermined aspects of the project. In this post I’ll detail some of the changes I’ve adopted after considering the survey submissions. I’m sure I’ll still have much more to clean up, but I’m hoping the community will be able to understand and accept some of the concessions and tweaks I made.

Important Note

The Pitchfork document isn’t simply me writing down my own personal practices. For my personal projects, I’ve been slowly tweaking and rearranging the layout based on what I’ve found to work and help me. If you visit any of my more dormant GitHub projects you’ll find a surprising lack of consistency.

Several of the practices and conventions in the Pitchfork document are things I haven’t yet done myself. In some cases this is because the prescriptions are not applicable to any of my work. In some cases the prescriptions are directly contradictory to what I have done in the past.

Pitchfork is the result of thoughtful look at both community experience and individual experience. In a few places the Pitchfork document deviates markedly from community opinion based on some well-made points brought up by individuals relaying their own specialized experience. These experiences are taken from Reddit threads, the C++ Slack, and the free-form responses filled out in my survey.

The points presented below (and the Pitchfork document in general) are not drawn solely from my own opinions. Rather they are the amalgamation of community convention and individual input.

Without any further ado, here are the results from the survey, and how they impact the Pitchfork draft.

Embedded External Dependencies

Original Question:

It is common in the C++ world to embed external projects within another project as a way to ensure the presence of dependencies. All external dependencies embedded in the repository should be placed in a subdirectory relative to the root of the project tree.

What should this directory be called?

The Results:

From the looks of it, deps/ and extern/ are completely out, which echoes a

lot of opinions from the first thread.

Lots of the written responses echoed the sentiments of the original thread, and

people expressed distaste at the “needless abbreviation” of extern/. I’ve

used extern/ in the past for the purpose outlined in the question.

The very first draft used deps/ as the directory name. This was quickly

revised to third_party/ after incorporating some convincing feedback about

deps/ being incompatible with certain systems which use a DEPS file as part

of the build system, where this will conflict on case-insensitive filesystems.

third_party/ and external/ both have strong support, with third_party/

receiving both the strongest affirmative support and the strongest negative

reactions. external/ received little in way of negative opinions, and close

second on positive reactions.

Since the draft (at the time, spoilers) used third_party/, and both

third_party/ and external/ have roughly equivalent support, it would be

tempting to stick with third_party/.

However, a common sentiment in the written responses appeared regarding

third_party/: Sometimes the items in third_party/ might not actually be

written by a “third party,” but were still being consumed as if they were. This

may not sound like a huge problem, but it would be enough to create some amount

of confusion, and lead some to look for a first_party/ to embed their

first-party external dependencies.

For this reason, and because there is less in way of opposition to it, the

Pitchfork draft now uses external/ as the name for this directory.

Source Directory

The Original Question:

C and C++ distinguish between “compiled” sources (.c and .cpp) files, and “header” files, which are only meant to be included in a final translation unit. There is debate over whether header files should live alongside their compile source file counterparts. Regardless, what should the name of the directory containing compiled source files be called?

The Results:

This was honestly the least surprising result, with only ten “Never!” responses

on src/, compared to 153 “Definitely!” responses.

The source/ name was a big “maybe”, with most people apathetic.

lib/? Not a chance.

An interesting contrast to the prior section, though, regarding “needless

abbreviation.” Not nearly as much objection to abbreviating source/ to src/.

Perhaps it is just the commonality of src/ as a directory name?

There were a few objections to using a directory explicitly for “source” at all, though. The rationale will be thoroughly explained in the Pitchfork document.

src/ will stay in the draft.

Submodules Directory

The Original Question:

Very large projects will often subdivide themselves into smaller sub-modules that can be consumed on an as-needed basis. For example, Qt has different modules that address different needs. In the process of subdivision, submodule sources should not be intermixed between each other, but subdivided within a subdirectory of the root tree to create a relative path from the root to any given submodule.

Submodules will not be relevant to all but the largest of projects.

What should the submodule path look like?

The Results:

libs/ is a clear winner amongst the given choices, but the written responses

tell me that I should take the answer with a grain of salt.

For many responders, the meaning of submodules was not conveyed effectively,

with many simply wanting to write the submodules together in src/. The

reasoning on why this is undesirable is written in the submodules section of

the Pitchfork document.

Several insisted that a project instead be broken into distinct separately managed projects and have them refer between each other. This is preferable in almost all cases, but the question is specifically written to target projects which do not do this for one reason or another.

Others said that this is unnecessary when/if we get proper package management. This isn’t correct, simply because of a mixing of terms. Project submodules is an orthogonal problem to dependency management.

A few who understood the problem proposed different names to libs/. I’ll have

to do a follow-up and address these.

For now, Pitchfork maintains the libs/ directory for this purpose, but this

may change in the future.

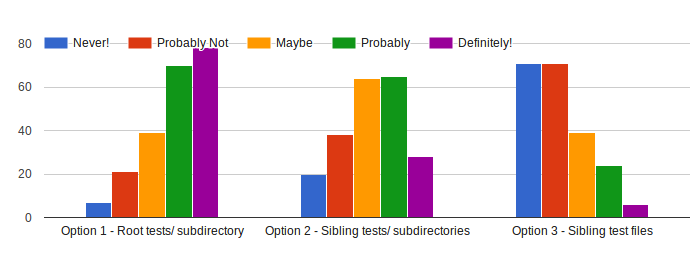

Test Placement

This one might get me in trouble.

The Original Question:

We all know we should be writing them, but where should we put them?

There are a few alternatives:

- Place all tests in a subdirectory at the project root. Call it:

tests/- Place tests in a subdirectory sibling to the code which they test. For example:

src/my_library/foo/tests- Place tests as sibling files of the physical component which they test, using a qualified filename to correlate test sources with their component sources. For example, the test for

src/my_library/foo.cppmight besrc/my_library/foo_test.cpp

The results:

This may be one of the most interesting results in the survey, simply because of the contrast between the responses on Option 3 and the ideas proposed by John Lakos, whose book Large Scale C++ Software Design and his various talks and presentations over the years directly propose using sibling test files.

When writing C++, I’ve never used sibling test files. In fact, I rarely see people who do use sibling test files. I was biased against it, but included it as an option for completeness. I also wanted to hear the justifications from those who use sibling test files. I didn’t expect to have my mind changed.

And it wasn’t changed, partially.

After some discussion on the C++ Slack, and considering several of the written responses to the question, I’ve actually come to a hybrid conclusion of options (1) and (3). Sorry Option 2.

Survey responders and several members of the Slack have brought to my attention an important fact: Not all tests are created equal.

Automated software tests can be divided between two types: Unit tests, and everything else. Not competing, but complementary.

Combine this idea with the ideas of logical/physical coherence (an idea proposed by John Lakos, explained thoroughly in the Pitchfork document), we can come to associate unit tests, which test a logical “unit” of the code, with a physical component. This association is very strong. Strong enough, in fact, to warrant that the unit test of a physical component should be co-located with that component in the source tree. This has further benefit when using merged header/source placement, since the unit test file of a component can be located exactly along with its two non-test source files.

Thus the Pitchfork document, despite specifically going against the survey results, and despite this author having never used them, prescribes the use of sibling test files for unit tests.

We can’t exclude non-unit tests. These are also important. The issue is that we cannot simply make them siblings in the source tree, as there may not be a one-to-one correspondence between non-unit tests and physical components. A test might test a combination of components, or may require data outside of the source tree.

For these reasons, Pitchfork also prescribes a tests/ directory in the root

of the project for non-unit tests.

Hope you kept those pitchforks sharp.

Executable/Library Separation

Original Question:

Larger application projects can have multiple executable source files along with non-executable library code. There is divide in whether and/or how this separation should appear in the project layout.

Should executable and library source files be separated?

The Response:

Clearly, the majority of respondents favor some physical distinction between library and executable sources when they appear together in the same project.

Perspectives of Library/Executable Splitting

Whether to do it may have a clear-cut common answer and is the least enlightening question, but the written responses are very interesting. I’ve chosen a select few that raise some interesting questions, concerns, and perspectives.

Static/Dynamic Library Splitting?

IMO, there are really three cases: static libraries and dynamic libraries (DLL or .so) are enough different, the answers for them will often be different.

An interesting point. Should we further distinguish between dynamic and static libraries? In my perspective this is a no, simply because many libraries offer the choice of building/consuming them in either a static or dynamic form, but the source code and API itself remains the same between them.

Why Libraries and Executables in the Same Project?

If a compiled library is used by multiple executable it isn’t clear which should “own” the library since obviously the executable belong in different locations. If the compiled library is used by only one executable, why is it organized in a library?

Should you split, even if just one executable?

Library is a dependency of executable, even if it’s just a front end for the lib. Factor it out each into a separate dependency and use a proper dependency manager.

Should the executable live in a separate project?

A few respondents offered justification for having the separation:

By splitting out the executable section, you basically force the idea of a re-usable library for the bulk of your code/library. This of course is a library-centric POV.

If you plan on providing a way for other programs to consume your code like say the openssl library for instance.

Mostly all code should live in library for better testing, executable should contain only glue code.

How to Separate Libraries from Executables?

As a follow-up to the previous question, the following question and alternatives were proposed:

Whether you affirm that executables should live separately or not, please review the three options below for the preferred way in which executables and library sources might be delineated. Choose your answer with the assumption that you MUST split your libraries and executables, regardless of your opinion of doing so.

The options below are based on common suggestions for lib/exe splitting, but additional proposals may be entered in the feedback field at the bottom of this page.

Option 1

Use

<source>/{bin,lib}::Use

<source>/libas the root directory for non-executable source files, and have those libraries be consumed by<source>/bin.

Option 2

Use separate root directories for executables and library sources. For example, one might place non-executable sources in

lib/and executable sources insrc/.If choosing this option, use the feedback field to suggest naming for these directories.

Option 3

Only use one

src/directory, but place non-executable sources in namespace-qualified paths and leave executable sources (main files) at the root of<source>, using the filename stem to correspond to the name of the executable which it will generate.

The Results:

People are not a fan of Option 3.

There seems to be an even split between Option 1 and 2. While more people answered “Definitely” to (2), more people answered “Probably Not” to (2). More people said “Never!” to (1), but more “Maybe” and “Probably” at the same time.

Depending on how you weight the five response values between the two options, you will get different results on whether (1) or (2) is preferred.

I actually favor Option (3), the least-favored amongst the choices. I can’t override community voice with just my opinion, though. The current work-in-progress Pitchfork tool is using this layout.

The division is so ambiguous that I have not yet addressed this point in the draft document.

In addition, several written responses proposed alternative layouts, the most

common two being <root>/{exe1,exe1,lib1,lib2} or src/{exe1,exe2,lib1,lib2}.

I was aware of these choices, but did not present them as options here as

these layouts present some conflict/overlap with the submodules section.

Problems and Implications of the Splitting Methods

Each of the splitting methods presents a unique set of problems and solutions.

For Option (3), wherein there is exactly one source file for an executable, there is no ability to use a directory structure or header files. This option strongly encourages, or even forces, a library-centric design for an application, where the executable source file simply defines the program entry point. Whether this is desirable or not is up for debate.

For Option (2), there is debate on what the root directories should be named,

and if there should be a mandated structure in the executable source directory.

Pitchfork specifies a layout for source directories for libraries, but says

nothing of how an executable should be laid out. Perhaps it is as simple as

duplicating the layout for directories for executables, where the layout simply

contains a main() function in the code? If using a split layout, do we put

include/ in the root? Will this collide with executable headers? Do we place

include/ in src/? That would imply a src/include and a src/src. That’s

pretty awful.

Option (1) presents an issue when using separate header placement. It

necessitates duplication of the src directory element. A library’s headers

will necessarily be placed in src/lib/include, and its sources in

src/lib/src. (Using merged placement does not present this quirk). There is

also general distaste at seeing lib and bin as path elements within a

project’s source code.

An Elaborated Option 2

After considering the possiblities, I’m now leaning toward option 2. Option 2 only specifies that there be separate root source directories, but does not provide any names for these directories. Perhaps giving these directories names can help change minds. This elaboration will only consider merged header placement.

We can assume that the source directory for libraries will be named src/.

Let’s use app/ as a new directory in the project root to hold executable

source files. In this layout, we might use top-level files in the app/

directory as executables that are only made up of a single source file. For

more complex executables, we can add additional subdirectories of app/ with

the directory name corresponding the executable name. We can treat

app/<my-exe> as an additional source directory much like src/.

Using these techniques, a hypothetical layout for Clang tools might look like something like this:

<root>/ # Project Root

# Clang Applications

app/

# Contains main() for `clang'

clang.cpp

# Contains main() for `clang++'

clang++.cpp

# Subdirectory for `clang-format'

clang-format/

# Sources for the executable

src/

# Contains main() for `clang-format'

main.cpp

# Extra sources:

clang/

format/

cli.hpp

cli.cpp

src/ # Main Clang library sources

clang/

stuff.hpp

stuff.cpp

format/

stuff.hpp

stuff.cpp

This looks pretty clean, and is easy to parse by tools and human minds. Tell me what you think.

Conclusions

The survey was very informative, and I’ve been making good progress on the Pitchfork document. I feel like it is approaching a point where the trade-offs are minimal, and the layout will support virtually all projects of any scale.

Future Pitchfork developments will be happening in

the pitchfork repository.

The latest rendered version of the Pitchfork document for the spec branch

can be found here.

If you are reading in the future, you may want a later rendering from the

develop branch here.

As of writing this, the spec branch is more up-to-date.